Industry experts explore new ways the metaverse is driving change in industrial manufacturing.

On a panel at Nvidia’s GTC conference this spring, Rev Lebaredian, VP of simulation technology and Omniverse engineering at Nvidia, expressed surprise that the industrial and manufacturing sectors have been the first to embrace metaverse technology.

“Our thinking was that the first industry to adopt it—because it’s a general platform—would likely be media and entertainment, and then next would maybe be AEC [architecture, engineering and construction], and the last would be industrial manufacturing, that they would be slower in doing this kind of adoption,” he said. “What we’ve been surprised to see is it’s almost inverted. The companies that are most excited and demanding to have these real-time, immersive digital twins are companies like BMW, who’s one of our most important partners for Omniverse.”

Lebaredian attributed the fast adoption to a threshold in technology readiness, combined with the manufacturing industry’s early realization that complex systems must first be simulated.

“This past year, I was surprised to see how much demand there actually is and how much interest,” he said. “For many of them, it feels like it’s existential. If they don’t figure out how to create better digital twins and simulate first, we’re just not going to be able to create the things we need.”

The panel of experts, moderated by Dean Takahashi, lead writer at VentureBeat, gave glowing examples of how the industrial and manufacturing sectors have embraced the latest technologies in this area.

Michele Melchiorre, senior VP for production system, technical planning, tool shop and plant construction at BMW Group, said that before adopting digital twins and metaverse technologies, production systems in factories weren’t connected—3D models of buildings, layouts and products were separate.

“With a virtual factory and the metaverse and digital twins, we bring all these things together, and we can use them together at any location where the people are,” he said. “That’s really where we see it growing.”

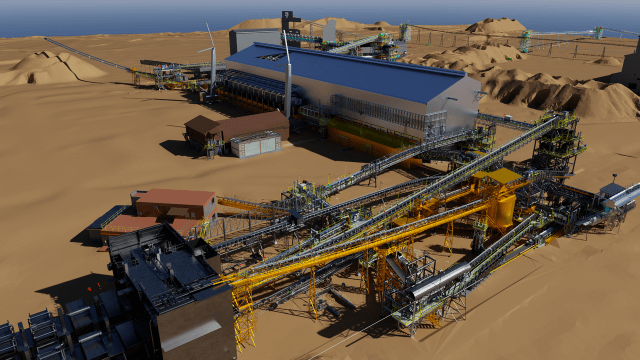

BMW has been working with Nvidia since 2021 and began global rollout of Nvidia’s Omniverse platform for industrial metaverse in Spring 2023. The automotive OEM is going digital-first–optimizing layouts, robotics and logistics systems before implementing them in the real world—in some cases, years in advance. The brand-new BMW factory in Debrecen, Hungary, is the first to get a full digital twin, with production scheduled to start at the site in the next two years.

Lori Hufford, VP of engineering collaboration at Bentley Systems, said that the metaverse has already demonstrated benefits to people, the planet and businesses.

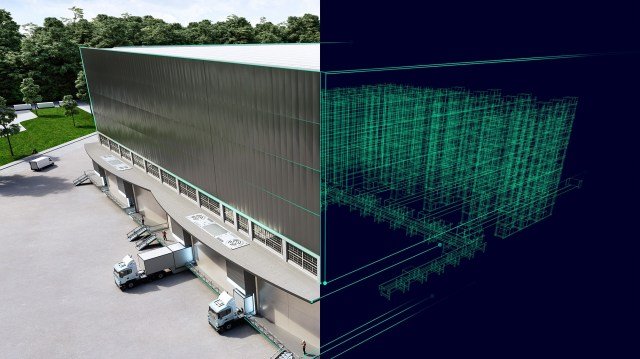

Bentley Systems is an infrastructure engineering software company providing its iTwin open digital twin platform for infrastructure and its LumenRT visualization software, among other products.

Hufford’s example, the Tuas Water Reclamation Project being built in Singapore by national water agency PUB, is “a one-of-a-kind, multi-discipline mega-project” to build a treatment facility for industrial and household water, she said.

“A project of this scope and complexity has major challenges in coordinating and communicating [with] up to 17 different contractors,” she said. “By leveraging iTwin federated models and Lumen RT for Nvidia Omniverse, project stakeholders have been able to review safety, quality and design challenges.”

Siemens Digital Industries Software CEO Tony Hemmelgarn said digital twins have come a long way since they started as basic models to see how physical parts fit together, evolving to cover functional characteristics of software and electronics.

With digital twins, the work is never-ending, because it needs to reflect its physical twin throughout its lifecycle, he said.

“One of the things that starts to come together, when we think about this idea of metaverse and digital twin and how we continue to improve this over time, is this idea of closing the loop, bringing the data back and forth,” Hemmelgarn said. “In other words, what I learn in the real world, how do I bring it back into the virtual world and make sure I can make changes and iterate through this process?”

Siemens has been working for years on the closed-loop digital twin, but the metaverse is bringing new requirements on top of existing physics-based engineering tools—factors like business systems, ERP (enterprise resource planning) systems, costing and sustainability, Hemmelgarn said.

“I would say the same thing is true in the metaverse, it’s never going to be finished, you keep adding to it, you make it more and more real,” he said. “I think some of the collaboration things on the front-end and high-end visualization, those are there. But we have a really long way to go to get to where we need to be.”

BMW’s Melchiorre said the same is true at BMW.

“If I have an assembly line, it doesn’t matter how good it is, we will always improve it,” BMW’s Melchiorre said. “You won’t get to an end. And I expect exactly the same for the digital twin, it’s endless. It doesn’t mean that we’re not happy with the result, but we always have to move forward.”

BMW uses metaverse technology for planning, setup and running factories, he said, and the digital twins are so good they allow even “Gemba walks”—a Japanese management technique that involves seeing the place where work gets done first hand – to be done in the virtual world.

The eventual aim is to have the digital twin reflect its physical twin so closely that it can even warn of problems before they happen, Melchiorre said.

BMW also uses metaverse technologies for collaboration on factory planning between teams in Europe, the U.S. and China. To ensure the systems can be used by all (not just those who have been extensively trained), they should be as easy to use as today’s games, Melchiorre said.

“We need something like online games,” he said. “That’s exactly what we’re doing and what we’re using. When you play these games, you have fun. If I’m sitting together with my engineers, they really have fun on these planning tasks, because they sit together virtually.”

Being able to work together in real-time means involved parties can discuss at the same time, speeding up the planning process so industrial systems can be realized faster. This saves money overall, because the planning part of each project is costly, he said.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across the metaverse toolchain to avoid multiple proprietary metaverses is a work-in-progress, Nvidia’s Lebaredian said.

“Most companies we’re talking to that are big players in creating the tools and these systems all recognize that not one of them is going to be able to create all the tools,” he said. “No one vendor can have the expertise in everything. So, there’s real enlightened thinking around interoperability that’s been growing… it’s not whether we should do it, it’s how do we do it?”

While the technical elements of making models interoperable is an unsolved problem, Lebaredian said he sees momentum in that direction overall.

“I’ll double down on the need for openness and extensibility at all levels,” Bentley Systems’ Hufford said. “It really is the foundation for ensuring that you have this ability for portability and for each platform, each organization to bring their unique value to solve bigger, more complex problems.”

Siemens’ Hemmelgarn added that the company’s focused on openness and interoperability.

“One of the tenets of my organization is you’ve got to be open, you can’t be a closed architecture, you can’t do everything for everybody,” he said. “Now, are there areas where I could say, if you use much of our solutions, the integration is much better and works much easier? Yes, at times. But you still have to be open to other solutions that are there.”

Siemens’ physics engines for 3D modelling are used by many of its competitors, he said, which adds value for the customer because it means the geometry never has to be translated.

However, customers including automotive tier ones are concerned about protecting their data and IP in complex relationships where they both collaborate and compete with other tier ones.

“That’s why it’s not just about going into an environment to collaborate, it’s also about making sure you’ve got the engines behind it, the data management, the configuration, the security and all the things that are already there to protect your IP and your design rights,” he said.

Metaverse evolution

What does the future of the industrial metaverse look like?

“Certainly, there’s going to be an evolution of communication, whether it be people to people, people to assets, assets to people, and even assets to assets,” said Bentley Systems’ Hufford, adding that machinery communicating its maintenance needs may reach an engineer trained in the metaverse.

Siemens’ Hemmelgarn said that similar to trends like the industrial internet of things and additive manufacturing, metaverse has been extremely overhyped.

“The metaverse has probably been overhyped for a while, but I think there’s real value,” he said. “It’ll be coming. It just takes a little bit of time.”

Lebaredian agrees.

“I think we’re on the cusp of something really, really big here. We’ve been working towards this for many years,” he said, adding that today’s combination of available compute, access to it through the cloud and connectivity to allow collaboration in real time are starting to converge.

“I think within the next year or two, we’re going to see some magical stuff happening with the convergence of these things,” he said.

This article was originally published on EE Times.

Sally Ward-Foxton covers AI for EETimes.com and EETimes Europe magazine. Sally has spent the last 18 years writing about the electronics industry from London. She has written for Electronic Design, ECN, Electronic Specifier: Design, Components in Electronics, and many more news publications. She holds a Masters degree in Electrical and Electronic Engineering from the University of Cambridge.