Home » Energy » Small Batteries Pose Recycling, Sustainability Challenges

Recycling and recovery of materials for batteries is a complicated topic, with different segments getting different amounts and types of treatment. For larger battery packs, such as fully electric or hybrid electric vehicles, it’s a well-defined and known issue getting lots of attention.

When battery packs wear out or the car is damaged, there’s a system in place for doing more than simply trashing the battery pack assembly, at least in principle. Of course, this doesn’t always happen as it should, but the success rate seems to be about 80% (except for lead-acid car batteries, which have a much higher recovery rate for many reasons).

For mid-sized battery packs, such as those used in smaller specialty applications like power tools, there really isn’t a well-defined recovery process. Yes, there are places where you can supposedly drop off those batteries, but I suspect many—if not most—don’t get the post-use attention they should.

There are also the widely used standard cells (AA, A, C and D) used in consumer products. These are almost always tossed out, as their constituent materials have little residual value—at least for now.

Finally, there are the ubiquitous coin and button cells, as shown in Figure 1. As with the other batteries and sizes, some of these are rechargeable and others are not. Anecdotal evidence shows that button cells also get tossed in the trash for the same reasons as other consumer batteries.

How many coin/button cells are sold every year? I couldn’t find an answer online; the few free reports I found gave the market size in dollars, which is both meaningless (is that OEM or retail dollars?) and irrelevant, as I was interested in the number of physical units.

The coin-/button-cell recycling challenge is due to the one-time use and non-chargeable primary cells, as well as the rechargeable secondary ones. The drained-battery problem even extends to rechargeable batteries, as they are not “forever” power-storage reservoirs. These batteries lose their capacity over time and use due to the many charge/discharge cycles they undergo in normal use.

The number of charge/discharge cycles is related to battery use and charging style, as well as the definition of “end of life.” The general wisdom is that you can get 500 to 1,000 cycles from a lithium-based rechargeable battery, but the actual number depends on many variables, such as charge protocol (often nightly), use/discharge rates, ambient temperature and other factors.

Furthermore, the formal designation for “end of life” is when capacity has degraded to 80% of the battery’s original value, but individual users may accept (tolerate?) more loss and reduced capacity until they finally say, “That’s it, I need to replace the battery.” Even worse, for some products, the cells—whether primary or secondary—can’t be replaced, and that has a major trash “ripple effect.” For example, Apple AirTags and similar “trackers” have non-replaceable batteries with a two- to three-year life.

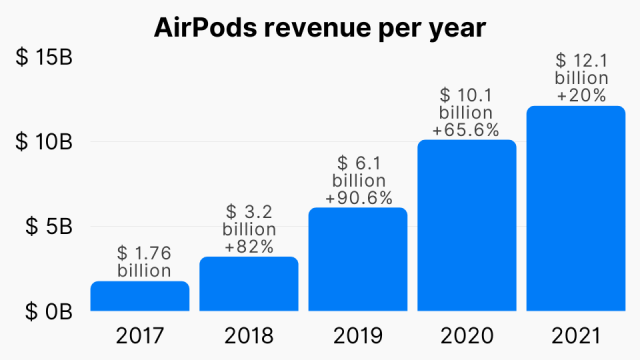

What products have these rechargeable but non-replaceable cells? One large application is Bluetooth-connected wireless earbuds, such as Apple AirPods. We’re looking at a lot of units for this product category alone. It’s estimated that Apple, with about half the earbud market, has sold over 150 million units to date. It’s a big source of a very profitable revenue for Apple, as shown in Figure 2.

Thus, while the numbers are a lot fewer than cars, which number in the low millions, all of those smaller-sized applications can aggregate to a pretty large pile of tossed batteries and more.

There’s also a bigger issue: The battery is only a part of the earbud problem. It’s bad enough that the batteries would likely get tossed if they were no longer viable. To maintain the integrity and reliability of earbuds, however, many of them—including all of the Apple units—are glued and sealed in such a way that the battery can’t be accessed. Some websites claim that a skilled technician can do it, but that’s a costly hassle and the integrity of the unit is compromised from that point on. The reality is that for nearly all users, the complete Bluetooth-connected, high-performance audio subsystem must be discarded.

Can this scenario continue? I can’t say for sure. Will users “rebel” or go with slightly larger earbuds that do have replaceable batteries, such as some Sony models? Perhaps it’s too early to say, as AirPods have been on the market only since 2016, but the bulk of sales have occurred during 2019–2020, so the first major batch of “tired” batteries is just getting underway.

The problem isn’t limited to AirPods: I have a standard $50 Black+Decker “Dustbuster” handheld vacuum that is always on trickle charge and is used only every few days. After about four years, its runtime is now under 30 seconds, compared with several minutes when new. The unit’s battery pack has four AA-sized lithium-based rechargeable batteries in a sealed housing, and they aren’t designed to be replaced (the battery pack is tough to access, and it needs cells with welded-on tabs).

My only options are to try to replace them, which is tricky but likely doable, or toss the entire vacuum unit, which is a real waste. Even if I hack in and replace the batteries, it’s a lot of work, and the average consumer doesn’t have the skills or inclination to do it.

It does seem as if the entire concept of tossing out batteries of any and all sizes, and perhaps the products they power, is a situation that can’t go on forever. But how long it takes until we get to the point at which nearly all batteries of any size are replaceable, collected and reclaimed is another unknown.

Perhaps regulatory authorities will mandate that the batteries in these devices be replaceable. Even if they do, will users send or bring the replaced batteries to a collection center? Again, I can’t say for sure.

Do you even see this as a problem? Should “right to repair” legislation mandate that all devices have user-replaceable batteries, except for special, unique devices in which the wrong battery chemistry would create a life-threatening or safety risk? Will environmental and sustainability rules require that sealed units, such as earbuds, have a firm return policy or perhaps a return deposit, similar to many beverage bottles?

Do you have some ideas about how to tackle the problems of these smaller batteries, as well as the throwaway products they often power? How can we address the issues created by “toss-out” use of non-rechargeable primary cells or rechargeable secondary ones, especially when the entire product must be trashed when the one-time battery is drained or the rechargeable one can no longer be recharged?

This article was originally published on EE Times.

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple EE Times sites and as both Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN. At Analog Devices, he was in marketing communications; as a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these. Prior to the marcom role at Analog, Bill was Associate Editor of its respected technical journal, and also worked in its product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls. He has a BSEE from Columbia University and an MSEE from the University of Massachusetts, is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.