Photovoltaic (PV) panels—also called solar panels—are a major resource for generating renewable energy, and there’s no need to repeat their attributes and virtues here. But they do have a major ongoing maintenance issue: They get dirty.

This contamination of their surfaces, generally referred to as “soiling” in the PV industry, leads to significantly reduced energy yields, especially in high-isolation arid and semi-arid climates. The problem affects large-scale solar panels as well as small-scale energy-harvesting applications.

There are many sources of this soiling, including dust, dirt, pollution, leaves and debris, bird droppings and more (Figure 1). It doesn’t take long for PV output to drop by 10%, 20% and then 30%, yet even a small drop is usually not acceptable.

What to do about it? There is no single solution, as it depends on the dominant type of soiling and the locale. Among the options are optimized cleaning plans, automated cleaning machines, anti-soiling coatings, tracking system modifications, PV module design, improved soiling monitoring and site adaption.

If pressurized water is used, it usually has to be trucked in from a distance (many PV installations are in sunny deserts), and it has to be pure to avoid leaving behind residue on the PV panel surface. Dry scrubbing is sometimes used but is less effective at cleaning the surfaces and can cause permanent scratching that also reduces light transmission.

Of course, neither of these options are “convenient” in installations like residential rooftops. Whatever choice is made, it requires some costly and challenging combination of labor, energy, water and complexity, yet it has to be done.

Now, researchers and commercial operations are offering very different ways to have the panels clean themselves. If proven viable, they represent beneficial options for the challenge.

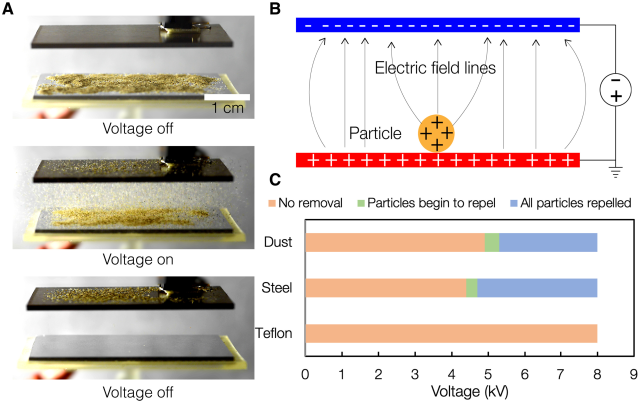

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), researchers have devised a waterless, no-contact system that they say could significantly reduce the dust problem. The new system uses electrostatic repulsion to cause dust particles to detach and virtually leap off the panel’s surface, without the need for water or brushes (Figure 2).

To activate the system, a simple electrode passes just above the solar panel’s surface, imparting an electrical charge to the dust particles, which are then repelled by a charge applied to the panel itself. The system can be operated automatically using a simple electric motor and guide rails along the side of the panel.

The system only requires an electrode (which can be a simple metal bar) to pass over the panel, producing an electric field that imparts a charge to the dust particles as it goes. An opposite charge applied to a transparent conductive layer just a few nanometers thick deposited on the glass covering of the solar panel then repels the particles, and by calculating the right voltage to apply, the researchers were able to find a voltage range sufficient to overcome the pull of gravity and adhesion forces, thus causing the dust to lift away.

Other groups have tried to develop electrostatic-based solutions, but these have relied on a layer called an electrodynamic screen, using interdigitated electrodes. These screens can have defects that allow moisture in and cause them to fail. While screens might be useful on a place like Mars, where moisture is not an issue, there is moisture and morning dew even in desert environments on Earth.

The MIT work is reported in extreme detail in the paper “Electrostatic dust removal using adsorbed moisture–assisted charge induction for sustainable operation of solar panels,” published in Science Advances; the paper not only describes the concept and its implementation but also has a detailed, analytical physics analysis of the multiple forces, electrostatics and fluid mechanics of the situation.

Another group is taking a totally different and completely passive approach. Fusion Bionic, a recent commercial spinoff from the Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology (Fraunhofer IWS) in Dresden, Germany, uses laser-surface texturing to create what are called functional surfaces. Its proprietary laser technology, Direct Laser Interference Patterning (DLIP), creates high-performance surfaces, reduced friction, improved contact performance and many more attributes.

In DLIP, laser beams are combined in a controlled manner to create a defined interference pattern within the target machining area. The pattern produced is much smaller than the laser beam itself, with typical resolutions ranging from 300 nm to 30 µm. A major virtue of the DLIP technology is that it enables functional surfaces to be produced at speeds on the scale of 3 square meters per minute—much faster than alternative approaches.

Due to the interference effect, there are areas of high intensity (interference maxima) and zero intensity (interference minima) within the laser beam. During processing, the material surface is modified only at the intensity maxima, while the remaining areas remain typically unmodified. The laser-texturing process used does not require any additional coating and does not affect the glass transparency.

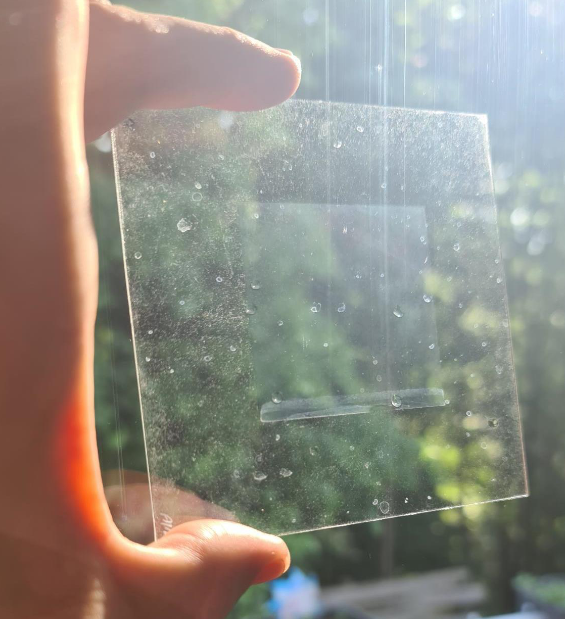

The DLIP approach has been demonstrated to enable selective self-cleaning performance using dirt on glass substrates (Figure 3). The critical factor about the process is that under the right conditions, with the glass surface at an angle of ~25°, no water is necessary to clean the contamination from the glass substrate.

The DLIP structures are created in a one-step process and are often comparable to known structures on natural surfaces like lotus leaf, moth eye and others. For soiling of solar panels, the design is modeled after the “lotus leaf” effect, which refers to self-cleaning properties that are a result of ultrahydrophobicity, as exhibited by the leaves of Nelumbo, the lotus flower (Figure 4).

The approach was evaluated with desert sands from the Sahara, Rub’ al Khali, Namib and Kalahari, as well as with dust of various types. It’s also noteworthy that the DLIP process is used for other, unrelated surface treatments, such as to minimize icing on aircraft wings, and Fusion Bionic’s website gives many examples.

Have you ever had issues with PV surface soiling causing excessive performance degradation, whether in large-scale installations, mid-scale residential setups or even small-scale energy-harvesting applications? What did you end up doing about it?

This article was originally published on EE Times.

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple EE Times sites and as both Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN. At Analog Devices, he was in marketing communications; as a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these. Prior to the marcom role at Analog, Bill was Associate Editor of its respected technical journal, and also worked in its product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls. He has a BSEE from Columbia University and an MSEE from the University of Massachusetts, is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.